Codex of a Lapsed Catholic - The Francés

Notes from a 2023 walk on the Camino Francés, these reflections mark the start of a longer journey. Dispatches from my 2025 Camino del Norte and Primitivo will follow.

Week One

No good deed goes unpunished

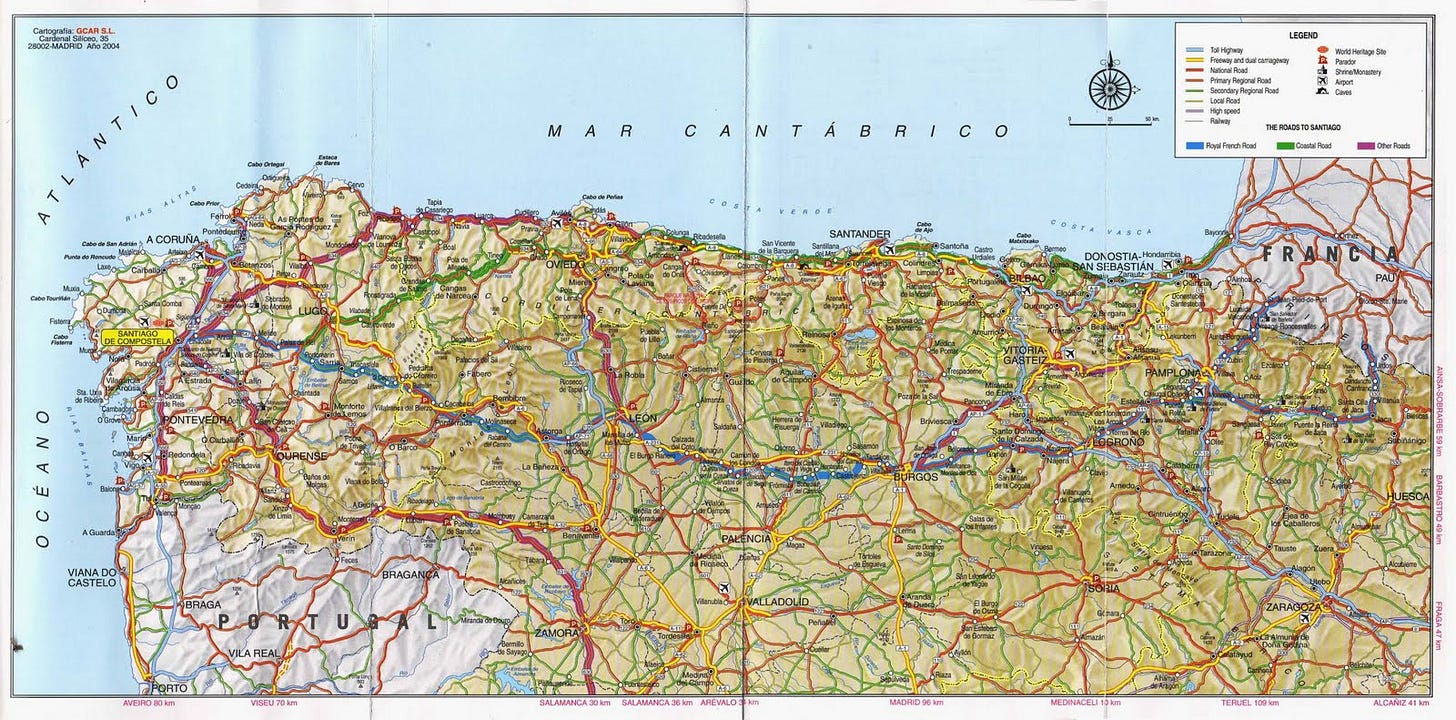

I’ve been intending to walk the Camino Frances for years, and I am finally doing it in the Year of our Lord 2023. For those who haven’t heard about this ancient pilgrimage, it's a 500 mile/800 kilometer walk from France over the Pyrenees and across much of Northern Spain.

It all started in the 800s when a hermit named Pelayo claimed to have been guided to the bones of St. James by a great field of stars (The Milky Way) leading him to what is now Santiago de Compostela, Spain. It was then occupied territory of the Arab Moors on an extended visit from North Africa. Charlemagne had done his best to dislodge them at the outset of the centuries long Reconquista, but some enterprising young clergyman figured that an old-fashioned pilgrimage like those to Rome and Jerusalem may bring attention to the occupation-situation. Pelayo was canonized a saint and the pilgrimage to Santiago ran roughly along durable Roman roads the trails of an earlier pagan trek to what was thought to lead to the end of the Earth in nearby coastal town of Finisterre.

Arguably, the Camino Santiago de Compostela was a public relations campaign to lay Christian claim to northwest Spain. You build a church with A-team apostolic relics and the pilgrims will come—in numbers. And that they did. Along with infrastructure, surrounding economies and new settlements. I’ve been walking their trails the last week.

Some will say that the success of the Camino de Santiago emboldened the several armed pilgrimages to Jerusalem and we all know how that ended up. At its height in the 1200s, the Camino attracted over 100,000 pilgrims a year. I don’t know where this comes from, but I didn’t make it up. This at a time when the estimated population of London was around 50,000, and the environs of Paris contained 110,000 souls.

Pilgims or Peregrinos now arrive in various states of purpose and preparation. I've met Italians, Japanese, Chinese, Koreans, French, Canadians, Russians and a preponderance of self-identified secular Irish, not American Irish, but real Irish people. Two on the first day.

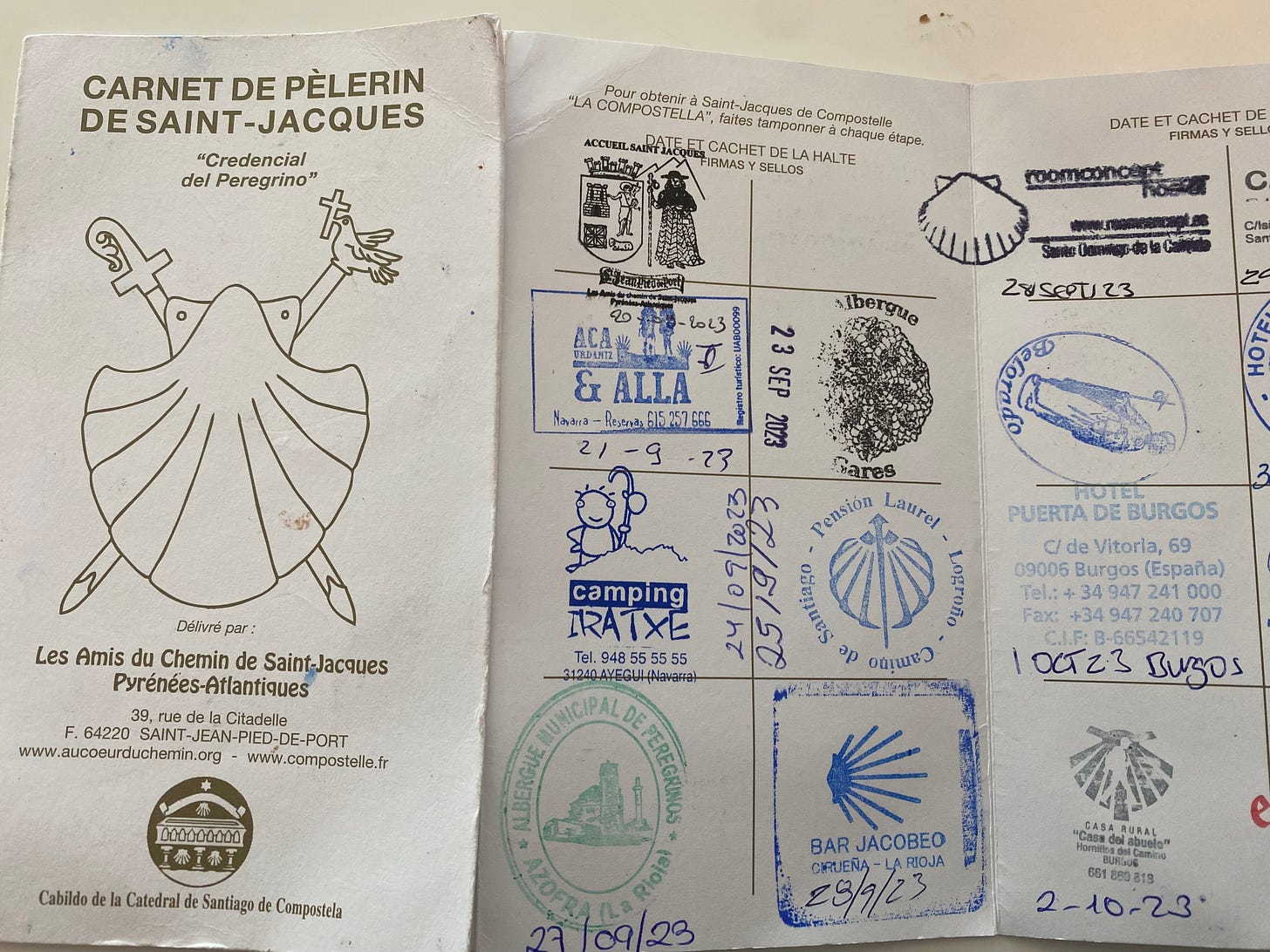

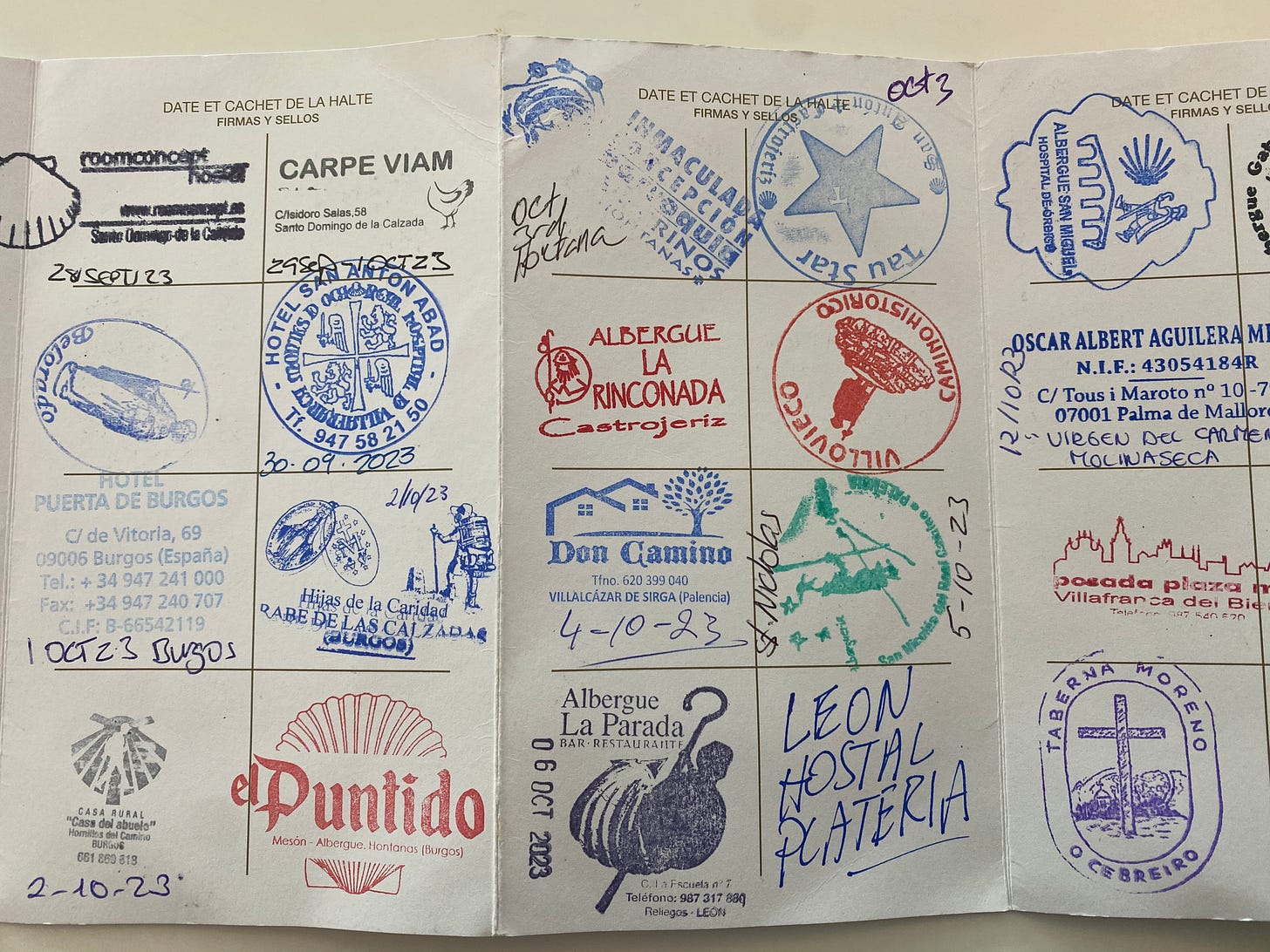

My departure was delayed. I spent five hours on the tarmac in Montreal for vague repairs, and two more hours as a fickle passenger decided last minute to get off the plane. You can imagine the fully booked passenger cabin wasn't pleased, but after about hour fours of mutual discomfort I noticed passengers began to acknowledge one another with a nod. As if an ordeal is more tolerable when recognized and shared with others. By the time I got to that mouthful of a departure city St. Jean Pied de Port, I'd exhausted any desire for static introspection. I started late in the day on September 20th. Nearly the last of the 1250 who departed that day.

I was relieved to meet another pilgrim climbing the hill on the Napoleon Route. I was trying to take a photo of a donkey sad-eyeing me from the other side of a barb wire fence, when I hear: are you negotiating rates to the top of the hill? Sean had a friendly Irish lilt. We chatted for a spell. He revealed he’s here because he's always felt guilty about his good experiences. He wants to see what that's all about. It's his Camino—a common phrase you read in books and forums. It's YOUR Camino to walk or ride as you wish. Others are reminded not to judge. I liked Sean, in his mid 60s, curious and game for the whole distance. But, he already had some pain in his knees. I slowed down intentionally to avoid a day-one shin splint injury, and we connected on our Catholic upbringing, secular adulthood and residual sentiments. Until an English couple joined us and their barely functional competitiveness more or less took center stage:

"We'll see how far we get, maybe Santiago, all depends on Lilly's ankles, they're weak…"

—or her later retort that seem somehow related:

"We are in transition now and moving to a larger house because Jack has so much stuff everywhere that he's unwilling to part with..."

They laughed uproariously when I stepped in cow dung along the road. These were obviously Benny Hill English, not the Monty Python variety. I can laugh at myself like the best of them, but they brought it up a couple more times and I'd had enough. I left everyone at Orisson and sped up a bit. This social experiment with people wasn't going well.

Over halfway to Roncesvalles or Valley of Junipers, and there are a lot of prickly junipers. I met another Irish fella, He looked like a Viking who’d ventured too far from the boat. An immense young man with tribal tattoos, sides of his head shaved with a weave on top. We walked together for a while. He’s a teacher and Irish Republican from Dublin who devours history, entertains the mystical and listens to Joe Rogan. He said his grandfather was an IRA man recruited to fight Marcos during the Spanish Civil War. He’d crossed into Spain over the Pyrenees like we were doing. We talked about colonization, the Troubles, the long memory of the IRA and their various methods and sources of funding. It was you lot who kept all that going, don't you know, well you and that nutter Qaddafi.

As Colin began to tire and night fall crept in, I knew I couldn’t just leave him behind. We were low on water and surrounded by thick forest. Moss grew on twisted oaks, where Colin said the fairies hid in waiting. Colin shared with that me in the past couple years he’d lost 150 lbs and suffered two strokes, and had been given his last rights. His ankles were beginning to swell. I suspected it was his first and last day on the Camino. We marched on and made it to Roncesvalles before nightfall where we enjoyed a beer and burgers at a cafe along the road. We'd finished the most challenging stage, I reminded him. He video-called his mother to tell her about it, I met this American fella who helped me down. I waved to his proud mother who looked younger than me. He later got himself checked up on in a hospital in Pamplona and ended up flying back home the following day. I’ll miss him, but we’re on Whatsapp.

I barely got into an albergue (hostel) in time. An English guy, Ray, was kind enough to open the locked door for me, as the manager had already left for the evening. When the proprietor returned, I endured my first camino lecture about respecting albergue hours from a fleshy young guy in tight pants. I was shown to the top bunk of a full dorm room. At one point there were three people snoring at the same time. It sounded like a symphony, a chorus of baby dragons—slithering reptiles gasping for air. I didn't sleep at all.

Second day, I walked in the rain with Ray, who had traveled the world in an Instagram van and is currently living in Brandenburg just outside of Berlin, surrounded by right wing hooligans and Ostalgia for the DDR. He explained his love for the game of cricket – and like the game itself, that took a while. I enjoyed Ray's company, like most of the English folks I met they don't start digging around anywhere near your personal life nor ask the WHY ARE YOU HERE question.

That evening at another full albergue, a sporty woman about my age—Connie—occupied the bunk across. She revealed a thirst for personal inspiration. She was the CEO and founder of a very successful market research firm, and wife of a presumably successful husband, with whom she sails the world both working remotely. I suppose on a boat at sea, everyone is working remotely.

"I'm not sure if I want to…" — she said, stopping herself, as if the mainsail swung overhead for a new tack — "I am going to continue. We are just going to get a bigger boat."

Then came the flurry questions for me, as if she'd exposed too much, like what do I do, and did I read Prince Harry's book, as he's her new client. She was tallying some hidden scorecard as her less than spiritual bonafides dopped fast and hard: numerous loyal employees, corporate passive income, next professional challenge, several properties in Vancouver, etc... At the communal dinner table of a dozen or so pilgrims, she took a lull in conversation to suggest

"Let's go around the table, there's something my husband and I do every night after dinner: we cite something that challenged us and something we are grateful for…"

I bit my lip. I so wanted to go first. I'll say I'd find it challenging to be alone on a boat with you, but I'm grateful your insufferable husband isn't here too. Next?

The next morning, I started before dawn, and walked deeper into Basque Country. I took a trail along a rough water brook — alone. It was glorious. I had the whole trail to myself, the music of water and silence. Hours later stars gave way to sunrise. A talkative black cat crossed into my path and then trotted ahead, leading me into the next town. Reminded me of a cat I had for seventeen years, Cairo, the first visit from my already lived-life. I wasn't around when he died. Someone held a cell phone to the cat's ear as it was breathing labored and raspy. I'd said he could go if he wanted to, he was a good cat, and thank you for being in my life. I remember sitting with a Nokia in hand, as cars on Pico whizzed past me, parked there on a busy street as my cat died a thousand miles away. Visions and visits from a life lived were to show up again.

I reached a public fountain, then turned to look back, and the cat was gone.

Now I leave at 5am to avoid the crowd. I've always been a fast walker. I'm using it to escape the staggering raw humanity around me, as incessant as a zombie apocalypse in colorful rain gear. I wondered on my first day alone that if this pilgrimage was not just a crusade to touch something that was holy, but also, a trial to keep and protect something divine that you already carry along deep within— like the walk to Oz, and the wizard's prescient rewards.

I was moving quickly through the twilight one morning when I met Franco from Rome, a slight man in his 60s who shuffled midfoot with a hitch from losing several toes. He had a fluorescent yellow windbreaker. Franco was the dopple-ganger of a Vietnam veteran I know who was once assumed dead, his position overrun by the Vietcong. He was able to blink before they zipped up the body bag. I met him in Florida once where showed me I could hold my breath longer than I thought, swim deeper, dive for abalone shells and spear dorado like he did for money after his discharge in the 70s.

Franco passed me after asking directions. He carried no phone nor maps. I sped up to walk with him for a while. We didn't talk much, but managed to communicate with a kind of Spitalian mix of basic words. Franco communicated that he walks 45 km/day. 28 miles. A day. I'd say that Italians were the most serious of the pilgrims I've met. They generally started earlier and walked faster. Americans talked, Italians walked.

I'm not a hagiographer, but I read that the medieval hierarchy of saints topped off with the original crowd from the Holy Land, then came the venerated Italian saints—closer to Rome and the Vatican, I suppose. After that came all the rest as faith in miracles receded with distance from Jerusalem. Even hometown religious heroes aren't really taken that seriously. I walked 47 kilometers the next day to Logroño and ended up with the first of my troublesome blisters. Yet, thanks to St. Franco, I found I could walk faster and further.

On my 6th day with over 100 miles in and the most common question is still Why are you here? We're like inmates in a penitentiary. I imagine it was easier to answer that question in the Middle Ages when everyone was basically looking to knock some time off their stint in purgatory—voluntarily or clerically directed. Now it’s a bit more complicated. Many modern pilgrims are in a state of transition and looking to punctuate a life change with a chance for deep personal reflection, and then tell everyone about it like I'm doing now.

There are the retirees coupled, sinuous and grey with the hard-earned ability to endure life's vicissitudes and clear their calendar for up to 40 days. And there are the lone-wolf repeaters who fell in love with the process, as well as the youth looking for a spiritual experience or free therapy. I heard someone say, I'm so glad there is the freedom here to tell a stranger anything. Not sure what guide book that came from but some do seem to be a yearning for an interaction with anonymity. What’s said on the Camino stays on the Camino isn’t an actual thing. The Camino Memoir is a well-trodden genre starting with a section of the medieval Codex Calilxtino attributed to Aymeric Picaud. A millennium later came Jack Hitt's Off The Road in the 1990s. Then reigniting secular popularity in 2000 with Shirley MacClaine’s book The Camino – a Journey of the Spirit, and most recently actor/director/writer Andrew McCarthy's Walking with Sam.

A common greeting to other pilgrims is Buen Camino. I’m hearing less of it lately as I progress along. It’s as if like everything else we’ve been tunneled into our own personal silos of experience. Well, it was a sweltering 94F on the Spanish Mesa today so maybe that had something to do with it. And out there with blisters forming and no one around, I asked myself why am I doing the Camino? I told myself--I was occasionally talking to myself at this point, I'd like to reengage with my Catholic faith and find personal meaning and purpose in the practice an ancient ritual. Brilliant. The ‘Camino provides’ as they say. To be frank, I really just want to lose some weight and see what happens out here.

Buen Camino

Week Two

The Things They Carried

Karissa is from London. Fearing her phone battery might drain unexpectedly, she brought an actual printed picture of her son in a blue school uniform. She wants to finish in the next few weeks to get back to him. Though she says she has family support in the Jamaican community, she doesn’t want to leave him in the city that long.

She carries chapstick on a string around her neck and a recent failure. A non-profit she’d founded that empowered young girls was forced to shutter. Unlike many on the Camino with affluent choices and higher spiritual aims, Karissa carried some anxiety about her future and job prospects most of which were away from the UK. “I’m just tryin’ to live really.” She travels light, except for an oversized two-prong travel adapter that she either borrowed from a friend or bought twenty years ago. She is making good time and currently one stage ahead of me. If the camino/life metaphor holds, it feels as if she has moved into another realm, or maybe leveling up in a video game with a higher status, more weapons, and useful magic.

I met Richard from Australia loping along a dusty road into Santo Domingo. He was in his early 70s. He carried a small backpack along with some of the other road runners who ship their heavy supplies ahead to the next hotel or Auberge. He carried an apple watch and a large tube of 50 SPF sunscreen. He’d already had a melanoma the size of a pancake removed from his back. He was in the import/export business and made a living moving overstock for various luxury goods companies. He’d just lost a lawsuit over some marketing infringement that appears to have also taken a pound of flesh. I’m here though, he said cheerfully over a beer after the day’s walk.

They carried smart phones, and chargers, spare batteries, passports, pilgrim credential—cards with spaces for ink stamps, quick dry clothing, rain gear, safety pins, sewing kits, clothespins, soap, toothbrushes, floss, moleskin, gauze, scissors, iodine, band aids, extra socks, quick release shoe laces, flip flops, chamois towels, sleeping bags, yoga pants, long pants and shorts, thin socks and runners. They brought children, pushed strollers, wrote memoirs, painted postcards, flew drones, carried pens, notebooks, sketchbooks, guidebooks, backpacks, water bottles, bandanas, floppy hats to block the sun, walking sticks, hiking poles, sunglasses, bananas to fight muscle cramps, and everyone had a palm sized white scallop shell attached to their packs that were traditionally brought on the return from the beaches of Finisterre, but everyone more or less skips over the walking back part, and chooses to bring the scallop to the sea.

On the road out of Santo Domingo I sided up to Kent from Texas who was once a navy medic with tier-one operators. He wore a salt and pepper beard, maroon gortex jacket, and carried ibuprofen and lessons from a failed marriage. You have to be there, not doing shit for Uncle Sam all the time… He swore by a knee brace that keeps his patella in place. He has a new job and a new girlfriend who is supportive of his pilgrimage, or he claims, isn’t sure she wants him around.

He’s also a civil engineer like the namesake of the town of Santo Domingo de la Calzada- Saint--Dominic the Engineer who built much of the Camino infrastructure through the region in the 11th century—this after getting rejected for admission into TWO Benedictine monasteries. He made the locals proud howerver. They still keep a live chicken and rooster in the church to commemorate a milagro or miracle in which St. Dom freed a wrongly accused young man by bringing his Moor captors' chicken dinner back to life dancing, clucking and crowing on the table.

The other St. Dominic (de Guzman) from a century later, founded the Dominican Order to adapt to the increases in city living. He was patron saint of astronomers and scientists, lived in France and claims to have met the Virgin Mary--who gifted him a rosary.

Kent is not a tall man but he has a booming voice. He offered useful solutions to my bursitis and blisters. Having done it before, he said the Camino has personal stages: physical, emotional, and mental. Pilgrims pass through them in any order, he says. I wondered if there was a spiritual stage, or if that was part of the mental stage, or all of it. I clocked the omission and kept it to myself.

Arana was an early 20s influencer and Pilates instructor. She carried an iPhone 12, bite size external microphone, selfie-stick adapter for her trek pole, and a tripod the size of a tarantula. She was the only woman in a dormitory room of about seven men. She's Russian, but is quick to tell you she is not living in Russia at the moment. Somewhere in the Balkans.

"I feel like I am surrounded by lions," she joked just before lights out. Guisseppe, a greying, rail thin publisher of rare books from Naples in the bunk below her carried some kind of crunchy snacks in a crinkle-prone bag which he offered to her as we all settled in. Unfortunately, Arana liked them and the crunching continued along with Guisseppe's seductive banter.

"Exercise is gooood for the buddy," he said, with a creepy hushed voice.

"Pilates is restorative and progressive," Arana replied, appreciating the interest.

"My booouuuuddy will neeeeeed some restoration aaaafter the Camino."

This was getting kind of disturbing, but much respect to Guiseppe from Naples for living up to any smarmy cliché his name may suggest. Arana zipped up her sleeping bag and the conversation petered out.

I'd spoken with her earlier in the courtyard. She had invited me to have a drink with her and Sergei, another Russian she just happened to meet along the way. Sergei didn't talk much. He was in his 40s, close cropped hair, fighting shape with an amputated left arm below the elbow. He had half-mast eyelids that could remain still watching a puppies play or a nuclear mushroom cloud form in the distance. He had the blue strips of tape on his calves that are supposed to help with shin splints, but he didn't look like a guy who could feel pain, nor his own shins. Sergei was early to say he wasn't living in Russia either—Brazil or someplace.

"We don't have very many options for VISA these days," Arana said, mournfully. "I would need a sponsor to go to the USA."

She'll probably find one. Arana was a stunning young woman, lithe, blond, blue-eyed, with translucent skin like a lost Romanov teaching Pilates in exile. I wondered how much her parents were paying this ex-Spetsnaz operator to accompany her on this trip, probably not enough.

Merlin is 79, he carried a small d-ring attached to his pack that held only a smaller circular key ring. As he walked it made a light dinging not unlike he sound of a distant flock of sheep. I'd gradually caught up to him and chatted as we negotiated a rocky trail together into Burgos. He was from Lancaster, PA and his parents had left the Amish community in the 1950s. He’d never gotten to know his grandparents nor aunts and uncles as his family was cut-off from the church clan. He’s hoping to arrange a Camino with his two brothers next year.

I thought of the Amish in Northern New York who walk on the side of the highway from farm to farm, village to village. Merlin stopped to treat a hot-spot on his toe with some Neosporin. Everyone has their own foot management strategy. Some use Vaseline, Tiger Balm, or even Vick’s Vapor Rub to keep them lubricated. I prefer to keep mine dry. Burgos hovered in the distance like a mirage for two hours as I began to gauge visual distance.

El Cid probably walked this same road. It's the birthplace of the celebrated 11th Century Spanish knight. Known for battlefield heroics against the Muslims during the Reconquista, he later fought against the Christians as a mercenary. Spain is complicated. Charlton Heston played him in the movie.

I ran into Luther the chef from Denmark along the trail a few days later. He was on an important phone call and waved me on. He carried a banana, chocolate bar and a can of Coca Cola. We had met earlier in the town of Puente La Reina and shared a beer while locals agitated cows to run in the streets. They released a few bulls, but it didn’t look dangerous. The animals couldn’t get a good footing on the cobbles. Young people in matching t-shirts and bandanas dodged in front of them, proving their bravery to each other. A brass band played in the town square. A Dutch woman in blonde dreds, Jana, said that she doesn't judge other cultures, but that it seemed cruel, disturbing and pointless. We agreed. She took a drag of her cigarette and walked away.

Luther said he closed his popular restaurant at the height of its success after his cookbook was voted the best in Europe or the world perhaps. Like many, he carries along his success and other promising options. It weighs on him. He hopes for inspiration along the Camino for the next thing. Don’t believe it when they say Denmark is the happiest country, he says. It’s the socialism, it slows people down. After dinner he showed some striking solidarity by offering to help in the restaurant's kitchen. They were way behind on orders. His important phone call was for a family matter. He talked wistfully of his workers who’ve moved on from his restaurant. He's a sommelier. He loves The Rolling Stones. Luther likes French fries, but he doesn’t like walking sticks, nor the large white windmills on the horizon.

They brought their contradictions.

Though every hiking guidebook warns against cotton and how it holds moisture, Clara wore a blue flannel shirt. She likes the way it feels. In the front pocket she had a Sony recording device the shape and size of a piece of a Kit Kat. She looked like a young Kathy Bates. She’s from Indiana and studying theater in London. Her thesis project is long form theater. I mentioned how the game of Cricket can entertain fans for days on end—impressed with my ability to make connections yet feeling guilty for just repeating some new information. She didn't seem to be interested. She's recording herself over these weeks, her own musings and the shuffle of her feet along the trail.

"I don't expect a lot of money nor attention as a performer because of my creative focus, and my body type," she said.

I remember Kathy Bates telling me once on the set of a TV show, Valley, you look old today. And then that sparkle in her eye, and laugh from her diaphragm that lets you and everyone else in on the joke of taking ourselves seriously.

"You don't know what you can't do Clara, not yet," I said then I bummed some extra moleskin from her, and headed off like an addict with a fresh new ten-dollar bill.

She hopes to meet her parents to accompany her for the long dry trek through endless wheatfields on the Meseta into Leon. They're apparently bringing more moleskin – the coin of the realm out here.

And they carried small rocks and stones, representing their burdens, guilt, offenses, anxieties and yes, sins. I have two stones, one an angular flat rock that fits into the crook of my index finger, ready to be launched a great distance, and another small one round grey and flat about the shape of a quarter. I’m not sure if I’m going I to throw that one or not. I’m becoming attached to it, maybe a form of acceptance for whatever it represents.

Tomorrow, I leave the bustling industrial city of Burgos to cross The Meseta. I’m about a third of the way to Santiago. I suppose as soon as my blisters heal, I can move on from the physical stage.

Buen Camino

Week Three

A Restless Rest in Leon

I’ve taken a couple days off in Leon over halfway to Santiago. This weekend is also a huge festival for the city in which they celebrate their founder—Saint Friolin an 8th century monk whose sole miracle is purported to have rid the region of locusts. A little research reveals Saint Isadore and Saint Vincent Ferrer are also known as anti-locust. Miracles, like television shows and movies, have reboots.

The city parties on. A rowdy band of brass instruments and impromptu parades crowd the narrow labyrinth of streets in the old town. I didn’t sleep my first night. Amid the clamor, I’ve had some time to reflect on crossing the Meseta, the high dry plain in the north center of Spain that grows much of its wheat, corn and sunflowers - dried brown, stiff and bowed southward. Over that last week I covered 20-25 miles a day. I’ve set out at 5am, enjoying the starlight and the trail to myself.

I've become accustomed to the constellations around me. To the west was a kite struggling to gain altitude with a short tail of streamers. To the south, there is Orion’s Belt that looks like the mouth a small barking schnauzer. The Big Dipper stayed on my right, the edge of it pointing to the familiar North Star.

In the dark blue before morning, I walked for a while with a Brazilian named Gia living in Montreal. Love brought her to Quebec with a desire to learn French. Solo now, at least she speaks French. We chatted about Montreal for a while— a great city for walking, but she can’t understand why anyone would want to ever do this particular Camino ever again. A make-shift café appeared in a field around sunrise. We had croissants and coffee and chatted like civilized internationals.

Did you see the guy in burlap with the wild eyes, doing it backwards? Have you met the French woman who is a professional chocolate taster? Have you been to Montreal?

I promised I’d send her a map to Leonard Cohen’s gravesite that I’d discovered walking near the swank neighborhood of Outremont. She'd tried to find it herself, but like me, she was confused by the field of Cohen gravesites, as if fame would separate someone from their own name. Later on, I mumbled some of his lyrics: Jesus was a sailor when he walked along the water, and he spent a long time watching… The coffee was kicking in. She wasn't half-crazy, nor wearing rags and riches, nor feeding me tea and oranges. You walk fast, she said, you should go ahead.

The sun at my back, the sky grew into bands of purple, pink and yellow ahead of me and I slowed down a bit to walk with stocky man with a grey beard who was moving with some difficulty. Knee replacement is fine, it’s my IT band, he emphasized, not my hip, it gets tight if I don’t stop and rub it with a water bottle. His name was Mark as well, from Amarillo. Pleased to met a fellow Mark he shared a quote from psalm 37: 37 of the American Standard Bible version that he boldly recites to his wife whenever they argue. Behold Mark the perfect man… and behold the upright for there is a happy end to the man of peace. On the Camino, it seems, Texas never disappoints.

I made a point of going inside some of the churches along the way. One hot afternoon I ducked into the shade of an adobe style chapel that could have been the scene of character redemption in a spaghetti western. There was a woman at a wobbly table to the left stamping credentials and a nun, habit and all, who approached me with a tiny medallion on a string. She put it around my head and began what sounded like prayers, a blessing - un bendición. Sister Ignatia looked me in the eye as she mumbled things in Spanish. I walked out of there and squinted at the sun like Clint Eastwood. Nice try, sister… I tucked the necklace under my collar and walked on.

Later at an Albergue some others were sharing that they’d stopped and gotten the same blessing. I joked that my blisters got worse after the nun's benediction. Karen, part of a humorless couple said, That’s because she was praying for your soul not your feet. Despite the hours of bus rides to catechism, rote morning masses as an altar boy and the endless pasty wafers I’d consumed myself, I let that one go, and dodged her afterlife crusade.

I did wonder later on down the road, my feet in rhythm, sun at my side, thoughts wandering — if we actually owned our souls. A soul could be a repurposed Camino credential card stamped with evidence of attendance and good deeds along the journey for entry into Santiago cathedral. I have an easier time accepting that a soul is like a moral rental, returned in good condition just because it’s the right thing to do. Born Catholic, but leaning Stoic I suppose.

Days later I ran into Big Jim from Memphis who made a point of bringing up his strong Christian faith and dropping codes to test my zeal.

"Let me ask you this," Jim asked, "have you been to any of the pilgrim services?"

"No." I said, as shame crept in around me like an invisible gas.

"Well, you should really try, "he said, helpfully.

I distinctly remembered seeing him a week earlier scuttling up a single track outside of Pamplona forcing other pilgrims aside and practically knocking some off the trail.

A couple days later a well-intentioned English lady, in her 70s, in the bunk over me, handed down a leaflet with a flowing graphic of a robed man releasing a dove with outstretched arms. She whispered, you seemed to have a lot of questions about things at dinner, this may help.

Ah, curiosity, the hallmark of the damned. I pictured writhing sinners in a Bruegel painting poked by bale spears screaming questions into the hell fires of eternity. Her husband came over and kissed her goodnight, I heard a sloppy mouth-on-mouth kiss, as if he's still marking his territory.

Trigger Warning: The church people are insufferable out here. If I may cynically generalize, it’s the secular folks and cradle Catholics who seem to keep to themselves. It’s the Protestants, Anglicans, Evangelists and Baptists… out here selling their wares. It all derived from Martin Luther in the 1500s who wanted to take the bible literally and do his own research, and somehow came to the conclusion that all you need is faith, and they are still printing pamphlets. I'm a fan of old school Catholic good works, and deeds getting you into heaven. Let God look over your credential booklet and just count the stamps like the nice person behind the counter in Santiago de Compostela.

Nevertheless, I did attempt a mass at the Cathedral in Leon. I knew when to sit, kneel, and stand like I was riding a skateboard again - in Spanish. The gothic arena was filled with civilians sitting back through the whole thing like it was early innings of mid-season Red Sox game. I didn’t get much from the sermon besides esperitus santu , mea culpa, tolerance and respeto for ALL of my children—with that last bit seeming directed at me personally. And that was enough, point taken, Monseigneur. Leaving the service, I felt lighter underfoot, strolling out into the large town square where the annual social explosion continued for the medieval monk who likely preferred to be left alone to kill grasshoppers.

Like the rest of Europe subject to post Covid's Overtourism, The Camino is crowded, and will only increase in number after Sarria—the bare minimum starting point to receive a Compostela (certificate of completion) entering Santiago. I have heard that there are at least 400,000 who have walked the Camino Frances to Santiago this year. The same number who are reported to have crossed the Darien Gap in 2023 over the borders of Columbia and Panama into Mexico. With wild sociological reduction, I could say all of us are just looking for a better life. I wonder though, which of these two humble journeys Jesus would have chosen.

In other news, I left my trail shoes at the ruins of an old convent and switched to sandals: the footwear of Galileans and Roman centurions. My Teva mandles have made quite a difference on asphalt and rocky roads at 32 Celsius (90 F) where I ran into an inspiring older gentleman, a Korean novelist, Hee Song. He named his children after biblical figures, and was impressed that my full name Mark Thomas Valley contained not one but two apostles - and a prominent Old Testament terrain feature. He says he creates while he walks. He is thinking and discovering his fictional world as he ambles along, peacefully, brimming with content. We walked together for a while and didn’t say a word, in our own thoughts. It was wonderful.

Karissa of London is so far ahead that I probably won’t see her again. I had lunch with Ray the cricket fan today who’s managed his blisters well. Gia stopped me in the street chiding me for the map that I’d promised. Luther the Danish chef may catch up today at some point. Everyone seems to be everywhere at the same time. We are all on the same road.

John, yet another Irishman I met on a dark road one morning who pointed out that Romans used white stones to illuminate their roads. He finds it’s ultimately easier to stay with his own pace wherever and to whomever that takes him. I have ten days left of walking. The mountains, the rain and the crowds await. There are still white stones on city sidewalks. I'm wearing my lucky medallion from sister Ignatia, my feet have cleared up. I’m ready.

Buen Camino

Week Four

The Vow

Leaving the festival weekend in Leon, I set a goal to finish the next 300 kilometers in ten days. You walk long days. Luther the chef texted me over Whatsapp after I’d left him behind. Crossing through the castles and lore of Castille and Leon may have inspired my ambitions to customize my itinerary to my own personal pace and distance as I took in the scenery.

There were reminders of the Moor’s occupation: pointed and curvy Arab arches started showing up on crumbling walls, and at one albergue—couscous and hummus appeared on the pilgrim menu. Templar crosses, that stylized red cross on the Monty python knight uniforms was now stenciled on the concrete Camino way-markers.

The scorched sunflower fields gave to iron rich soil at higher elevations and then more verdant terrain as Galicia approached. I crossed the long Roman bridge into Hospital Obrigo to later read there was a certain knight from the town who, having been scorned by a local beauty, vowed to break the next 300 jousting sticks of whoever tried to cross that bridge into town. He succeeded as history goes, and likely inspired Cervante's Don Quixote. I wonder if after 100 joust-fights this knight had felt able to move on from his broken heart. But if knights made anything they made vows. It was the vows that made the man, keeping them built a reputation—the cash in hand version of immortality. Further upstream another intrepid knight vowed to build a dam for the father of his paramour. Things worked out better for him with his engineering and practical problem solving.

A day of solo walking later and I came upon a ragged brigand of younger people in the wee hours in the village of Molinaseca. I’d caught up to them, but lacked the energy to pass. So, I tagged along to a coffee shop. Where I met Luka, a young Berliner bored of Berlin, but—amazed that I was on the wall when it came down. Lela from Quebec who was Muslim and had just left the police force. Sarah the 19-year-old from Tel Aviv, anxious about her obligation to serve in the IDF just after the Hamas attacks. Dan the ski instructor from Banff who had his tactical gear and recreational weed well dialed-in. Martine was welcoming and having just moved to Oakland, excited at my mention of having lived in California. There weren't a lot of people from California on the Camino. Mostly Texas and the South.

Seems everyone on the camino was in flux back in the world, on the cusp of life changing options, except Dan who lit up for his morning blaze. The WHY question came quick with these kids no matter how vague the answer. I said I wanted to mark a transition from actor to writer, and lose weight, but after listening to them and answering more probing questions like: have you ever fallen in love with someone you were pretending to be in love with in a movie? I realized that if you want to travel fast, travel alone. If you want confirmation that we all fundamentally share very common hopes, wonders, fears, obligations and dilemmas then walk in a group. If you want to travel far—I’d recommend Ibuprofen 400 mg, it’s super cheap in Spain. Thanks Kent.

We passed a Templar Castle on the way out of town. “Who were the Templars?” Sarah asked. I’d just watched a YouTube documentary on my phone the night before so I summarized:

The Templars started in 1120 as a kind of Holy Land Pilgrim protection service chartered by the Vatican. Though they swore an oath to poverty, by the late 12th century they were landing some hefty mercenary contracts, and doing most of the fighting in Spain to get rid of the Muslims — who it was rumored to be deflowering 100 Christian virgins a year. As such their work was appreciated in the region. In addition, they essentially invented American Express travelers checks for pilgrims who didn’t want to carry cash across Spain, Italy or the Levant. Some of their land grants dot the region of Castile and Leon.

Though white supremacists have sought to co-opt their medieval heraldry, the Red Cross of the Templars still represents power and nobility in Spain. By the end of the 13th century, they’d gone a little rogue of the Pope and powerful clergy. Their leadership was burned in France on a Friday the 13th 1307. An event not unlike the recent plane crash that killed the leaders of the Russian’s Wagner group. Rule number one and two for non-state armies is still don't piss off the king, and don't shit where you eat.

We walked silently for a while. I don't like to be the educator in a group, but for a moment I felt like the cool parochial teacher who wears corduroy, takes students on field trips, and later gets fired for saying piss, shit, and deflowered virgins.

Back to my own pace and peace, I moved on from the group. Walking faster and further than your average pilgrim gives the disorienting sensation of traveling ahead in time, meeting folks who had started their walk even earlier.

After dropping a couple stones at Cruz de Ferro—small stones brought from home that represent burdens pilgrims hope to leave behind. The Iron cross thrusts out of a pile of rocks built up there for centuries. Some with notes attached and colorful momentos from flags to old ribbons and even small envelopes and painted rocks initialed with paint and marker pens, each as original as any source of shame, sadness or anxiety. I hadn’t really thought about what my burdens were, but I dropped my stones and moved on over the cumbre or summit of the highest point along the Camino. Acting and people-pleasing flashed as possible discharges but I knew it wouldn't be that simple. A start, yes, but not that easy.

I joined a traveler with a Canadian flag patch on the back of his pack. Even since my days in the Army in Germany, the Canadian flag was a sign of Canadian backpackers hoping not to be confused with Americans, or even more often—Americans not wanting to be confused with Americans. Horst as it turns out, was Canadian but born in Germany. We talked non-stop, finishing each other’s historical anecdotes. Like a couple of magicians trying tricks on each other. Not impressed with the show, but enjoying a kind of rambling fellowship. He described a complex upbringing—having coffee and cake with his Aunt Gerta in East Germany while a local Stasi officer subtly appraised his value as a possible spy or courier. Horst lives in Toronto, we agreed to meet back in the world at some point. He’s been writing prolific dispatches that I have to catch up on.

A couple days into damp and hilly Galicia comes the climb up to O Cebreiro where I was surprised with a swift inhale of emotion. On the final push up the hill into town I could hear bagpipe music playing, feint then stronger as I approached the summit along an ancient stone wall. The musician wore faded jeans and a red wind breaker—a somewhat jolting absence of kilt and plaid. I filmed him, dropped a Euro in his box and sent the video to Colin the Irish guy I met on the first day who’d talked with pride about the Celtic influence along this part of the Spanish Coast.

I looked back over rolling miles of farm and grazing fields, and sat next to a patinated statue of a naked woman — La Xana, apparently, a Galician water-woman who bestows fortune on those who offer respect. I was cordial. There were tour buses picking up those who'd just walked to the ruins at the top of the hill for the day. Buen Camino, one of them said kindly to me before getting on the bus. Like I was one of the wild attractions of the day's adventure. I don't know why I teared up, maybe it'll come to me later. I asked someone to take my photo. I'd clearly lost some weight and was wearing sandals with socks with a Dodger blue fanny pack. Who was this person?

I stopped into a nearby cafe for a stamp on my card and a Coca Cola. I tried a Galician empanada which resembled a flat beef pot pie. I walked another 10 kilometers that day. Soon I’ll be in Sarria where thousands more join the parade of stragglers. Rain is in the forecast. About three more days to Santiago.

Buen Camino

The Final Push

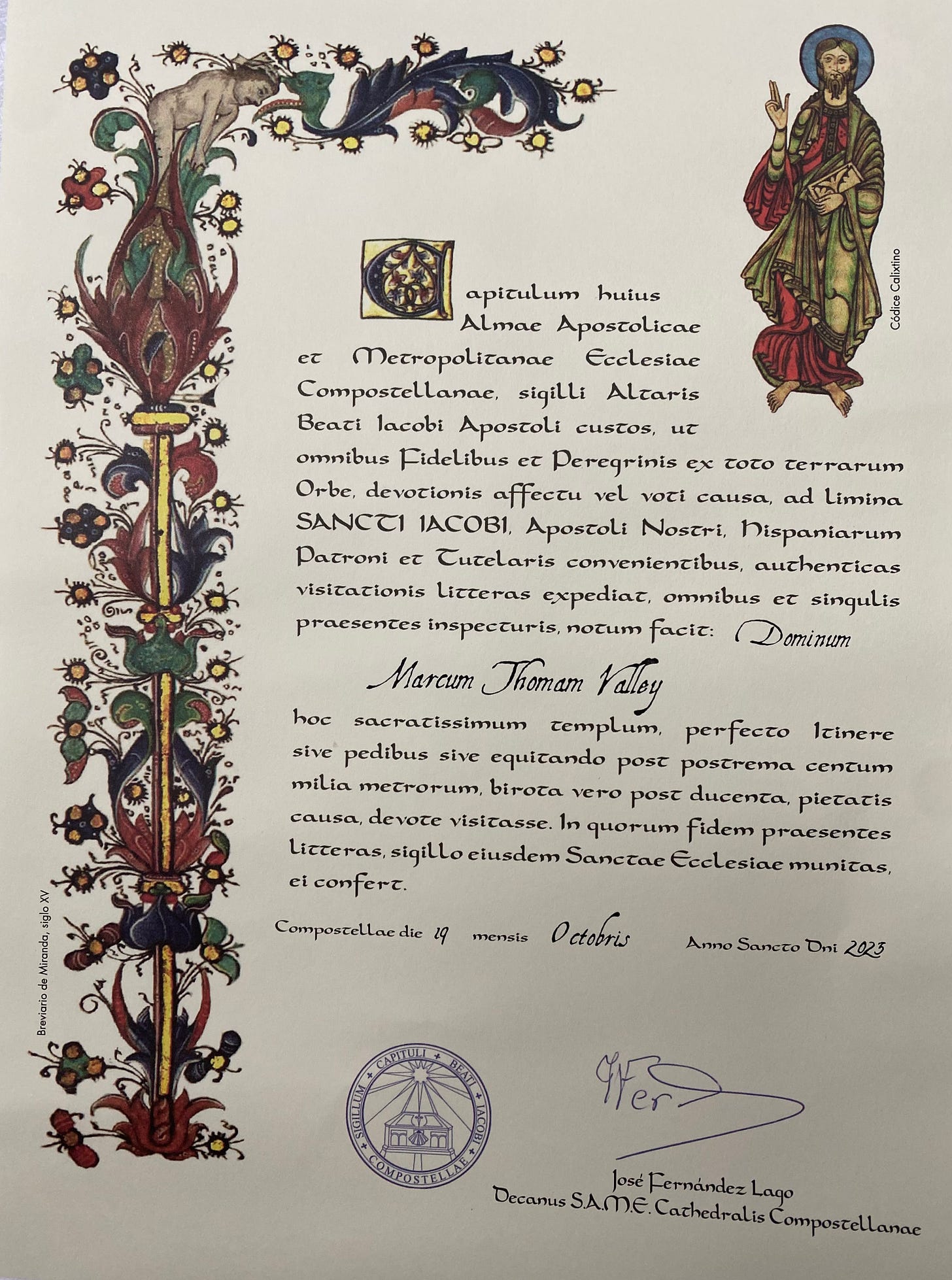

The Compostela

The final few days started with a drizzle, then rain and finally the last day into Santiago—the deluge. The trail was full of new pilgrims fresh out of Sarria to do the minimum 100 kms to get a Compostela. Their numbers were legion with ponchos pink, blue, black and green dotting the muddy trails and slick roads. My socks were soaked, my clothes reeked under my poncho but I was at peace, I was almost finished. Casi Alli – almost there.

Approaching the town of Melide, the rain let up and I slowed a bit to chat with a couple of voluble Americans who both worked for a homeless charity called Mobile Loaves and Fishes. They were part of a larger group, and higher purpose, it seemed. Sal, the older of the two in a Golden Pond Henry Fonda hat, had gotten Covid early on and spent five days quarantined in Burgos. The other, Miguel had apparently waited, or walked slowly until he'd caught up.

"Do you know the number one reason for homelessness in America?" Miguel asked. "Mental Illness?" I said.

"Nope."

"Lack of housing?" I offered. Genuinely stumped.

Sal deflected the humor, "you'd think, but tell him Miguel…"

"It's a lack of community," Miguel said. 'That's what we are bringing them."

They cited the national scope and success of their organization: MLF.org — I know, unfortunate domain name, and I'm surprised it wasn't already taken.

Sal and Miguel spoke of their founder with just a dash more reverence than I was comfortable with. Their founder, and they called him founder, was no longer walking with the group but traveled to towns along the way to join them for prayer and meals. I wasn't invited, but Sal asked leading questions about the homeless in Northern New York… We exchanged buen caminos. I walked on, glad to have met some valiant church folks doing good deeds.

On the morning of the last day, I awoke to the sound of heavy rain pelting a tin roof outside my window. My clothes hadn't dried overnight. I wanted to stay in bed. I didn't want to start and I didn't want it to end. The pension was relatively pricey, and didn't offer breakfast. I was grumpy, I slammed the iron gate and stepped out into the torrent. But it's hard to stay angry while walking. Someone along the trails had mentioned to me that walking staves off anxious impulses from the amygdala. I kept walking.

After a few hours of sloshing along in the warm rain, I stopped for a coffee at a crowded cafe. I made my way past smokers at the entrance, wet ponchos dripping on strangers, steamy windows. I found a table in a crowded dining area and dropped my pack on a chair. With my PWP: passport, wallet, and phone with me I got in line and waited.

It was late morning. Some were already ordering beers. This was the four-day Camino crowd. Upscale, prepared, impatient. Everyone was over dressed and disillusioned by the deluge that continued outside. Though it's harder to discern folks with their clothing these days, I noticed a lot of Spanish men wearing what looked like yoga pants. Like shingles, Spanish men don't care. There were several in the ruffling crowd somewhere with incessant meaty coughs that added some Covid-danger to the confined space. I didn't care either. I wanted my café con leche, caliente con tarta de Santiago – a delicious almond and lemon cake that all bars and café's seemed to offer in Galicia. I relished every bite and drop amid the discomfort bustling around me.

As I struggled with my poncho in the small covered area just outside the café, one of the smokers leaning on the wall—a quiet non-descript Spanish woman, helped pull it over my pack behind me. I said Gracias. She nodded, like someone from the plane on the tarmac in Montreal. Her offering of kindness stood out in that riotous cove where everyone it seemed, including myself, was fighting for their own brief pleasure.

I walked ankle deep through streams that covered the muddy trail that gave way to asphalt up to a park that overlooks the city of Santiago sprawling out below with spots of blue sky emerging. I took a shortcut across a field of grass, my first time off a road or trail in a month.

The sun broke as I entered Santiago. I soon ran into Tim and Lynnette a couple I'd met a day before on the trail and chatted with them for a while. We were just talking about you. Until seeing them it looked like I was going to finish alone, and I'd felt a little sad about that. The Camino provides. It was Tim who'd given me the tip for web link to apply for the ancient Compostela online ahead of time for my QR code to store in my phone. He reminded me to check the religious reasons box, If not you'll not receive a proper Compostela, only a certificate of distance and maybe a granola bar. He was funny.

We walked the cobbled warren of streets as lute and bagpipe music banged off city walls leading us to the plaza in front of the cathedral. I thought of all the folks I'd met along the way some who said they weren’t doing the Camino for religious reasons. Would they still be doing this if it was an old satanic pilgrimage? I doubt I would.

I dropped my pack in front of the Cathedral. Tim said "We did it," with some emotion in his voice. He dropped his walking sticks and hugged Lynette. I gave them some space. I felt like I'd already finished alone back on O Cebreiro for some reason. We took the obligatory pictures of each other with smiles and the cathedral spires in the background. We then picked up our Compostelas around the corner and had something to eat at a local restaurant where Tim spoke in rapid Spanish to the barmaid and Lynette looked on with admiration.

I was just happy I finished. I felt a general elation. I wanted for nothing. Proud and grateful I was able to walk for weeks, avoid and engage a wide variety of folks and share the finish it with who people whose company I enjoyed. Tim is English, and a physician with Doctors without Borders, and Lynette is a very talented painter with a certain New Jersey accent and voice that sounded exactly like someone for whom I used to carry a lot of resentment. I didn't feel that anger anymore. We had some more laughs, paid the bill and I headed off alone, Compostela in hand.

I passed bars and restaurants, filling up now already with pilgrims. My cold had turned into a familiar sinus infection that seemed also aware I had just finished—and now could finally make its best attempt to make me miserable. I found my hostal room—so many names for a place to sleep here. I then went into the shower fully clothed. It was one of those modern unmarked chrome piping rigs where you don't know which direction is hot and which nob will send water scalding your head or shooting up your nose. I figured it out and eventually felt the hot water drizzle over and under my walking suit.

I thought of the people I'd met earlier in the walk who were a few days behind, Ray the cricket fan, Luther the chef, May from Taiwan who I kept running into with her pink windbreaker, sunflower patch and stuffed animals dangling from her pack, Richard the Aussie, Gia the Montrealer, Margaret of Silicon Valley who sold her software company and had already summited the North Face of Everest, and Horst the prolific Canadian too. All still out there in the rain somewhere. I slept through the evening pilgrim mass where, apparently, they swung the famous botafumeiro - a large incense burning thurible. I resolved to watch it on YouTube. You can too. I needed the rest.

The next morning, I got to the church on time for 930 am mass and took a knee in the nave of the Cathedral of Santiago. I said an Our Father and scanned the altar, the gilded paneling vaulted up and spread in four holy directions. High above there were stained glass windows in the crown of the ceiling. Down the supportive piers were somber statues and gold angels stuck to the walls in mid-flight—all hovering over the altar and great repository of the bones and relics of St James the hero the Battle of Clovis, namesake and patron Saint of the destination of the religious migration of a thousand years. Though not the other James, James the Greater, the brother of Jesus Christ who stayed local in Jerusalem and tried to keep the new organization on track and was likely killed with rocks under Herod. That St. James, convinced by St. Paul, was ultimately credited for removing the requirement of circumcision and opening up membership to Christianity across the Asian continent into Europe. Where's his church?

Others in nylon and polyester were coming in and getting their seats. The early ones were throwing shade at the secular pilgrims passing in front of the altar without genuflecting. It was all a bit much really, the gold, the angels, the pilgrimage, the church people. I wasn't going to get a lot out of a mass in Spanish anyway. I'd now become accustomed to spiritual revelations while on the move. So, I did what I'd always wanted to do as a kid. I skipped out before it even started.

I slid through the gift shop where outside I joined a veteran camino-man walking toward the main plaza. He was stooped as if in a perpetual forward motion. His large canvas pack was covered with patches from every pilgrimage imaginable. I asked if was going to mass. Not me. He said. I'm just going to say a prayer for someone I met on the Camino. I didn't pry. Instead, I got myself a cafe con leche with a torta de Santiago. I took a photo of it and said my thanks. Wondering if all those food photos are just an acknowledgment, an electronic grace. I grabbed my backpack from my room in the Hostal Nomad and jumped into a cab to the airport. I watched the roadside whiz by, on roads I'd just walked. Soon I'd be flying through the sky to other places, places that I can't walk to. The world is too big for just walking.

Buen Camino

Epilogue

Eight Little Pillars of Wisdom

Your pace is your peace.

On the Camino you have a choice whether to engage with people. You can speed up, slow down, or even stop. Like boxing coaches will tell you—your legs will save you. It takes energy to engage and move at the speed of another. Minor annoyances need not be engaged nor addressed. I want to stay with my own pace toward my destination and goals - this life is my Camino.

If it won’t dry it shouldn’t fly.

A good tule of thumb for any clothing on a pilgrimage. There aren’t many secadoras or dryers on the road and folks charge a premium. Thinner socks, shirts and pants. Bring things that will hang dry overnight. I brought things I didn’t need and either shipped them home or left them behind. I bought things there I needed. There's not a need to pack perfectly. Bring worn in shoes, a good pack, sleeping bag or liner and moleskin—they're only things you can't really find easily.

Gratitude needs latitude.

I found there was a different degree of gratitude for getting what I needed, it’s more powerful sincere and rooted in sustenance. I don’t think it’s the same gratitude for chocolate. There should be another word for thanking God for nice things, things you don’t need. Keep gratitude focused on the basics - food, clothing, shelter, people, shoes, health, warmth, - there’s a different appreciation for the basics. Otherwise, gratitude seems like the price you pay to keep all your toys. Additionally, I used to think of gratitude as something you should have or should express, now I realize it is an integral component of enjoyment – and may have been there all along.

Read the room.

Your biting satire is killing my vibe, man. – something The Dude would say.

Negativity, the ability to carry it around for humor or levity, takes energy. To recognize it and appreciate the wit and humor, takes energy. I mean, I love a well-placed facetious comment, lifted eyebrow, or a dismal irony brought to light, but on the Camino I tended to conserve action and thought. Pilgrims aren’t necessarily an earnest horde plodding along, but I began to recognize that some already had all their fingers in the dam of self-doubt, and any trickle of dark humor could destabilize an already precarious stand-off. Even saying Camino Luvioso (rainy camino) instead of Buen Camino just didn't get the laughs I expected. It felt as simple as not pointing my finger at the dirt, but keeping hopeful eyes on the horizon. I thought of the only Italian I know — La macchina va dove vanno gli occhi (the car goes where the eyes go) – from The Art of Racing in the Rain. Just as we are what we eat, we are the quality of our thoughts.

The body will crave what it does.

I forget about sloth — the seldom enforced cardinal sin. Hard to believe there is a sin for actually just doing nothing. There were mornings I didn’t want to get up, but I could not sleep in. Not from some great stoic self-discipline, nor prayer to resist the temptation of the flesh. My legs just wanted to be on the road, my lungs wanted cool clean air, my eyes wanted the stars and the tingle of mystery that connects them. Those mornings I watched myself get ready and felt like I woke up after about five kilometers.

Meaning travels its own road.

We are spiritual beings, but I think we can feel a meaningful event before even understanding it. I had a cry at O Cebreiro. No reason, not the hardest day nor most important, but the bagpipes hit me in the feels. I don't have a particular connection to bagpipes, maybe it reminded me of the 80s film Highlander, and the soundtrack by Queen "who wants to live forever…" And the lead singer dies a few years later. Maybe that was it. That gets me every time. I don't know. I did know that the rest of the Camino was more or less downhill from there.

We don’t always know what everyone is going through.

May from Taiwan seemed like the happiest person, bouncing along the trail in pink and other colors. The second time I met her she was on a bench, shoes off along a dark early morning road. I stopped and asked if she was okay. She had blisters everywhere. Moleskin between her toes, obviously painful. I held my headlamp steady while she patched up her other foot. We ran into each other weeks later.

Roland looked like a retired legionnaire when we first met. A dashing smile as he explained in French where New Caledonia was, the former French colony. I saw him a week later hunched over unable to carry his pack, like Papillon before he jumped the wall, in obvious pain from his side somewhere near his liver. I shared some Ibuprofen and led him to a nearby Albergue. He finished as well. It’s impressive the pain some endured and overcame silently.

I met a cranky middle-aged fellow, probably a typical boomer who has too much money to spend and not enough time left, turns out he lost his son on the Napoleon Route after a bad storm hit the Pyrenees. He never knew him and chose to walk to finish what his boy had started—Or was that the plot of the Emilio Esteves film The Way staring Martin Sheen. I'm really looking forward to the sequel.

Our feet were the first filmmakers.

Once back in civilization, I started watching a police drama series on Netflix and could - not - stop. I marveled at the large screen and what it presented me. New and interesting people showing up, the camera sweeping past breathtaking vistas and cutting to shady locations across town, a story evolving and clearly building to some kind of ending that made sense. I was mesmerized and also feeling as if I were cheating at something. For the past month it was my legs that had to bring me to new locations, to meet new people, carry me through events both quotidian and meaningful, and ultimately walking as far as the end where I was left to find my own meaning and resolution. I'm still looking.

I lost 15 pounds though, not bad.

Buen Camino,

Mark Valley

Buen Camino, Mark. Leigh Heiss and I did 100 KM of the Camino in September of 2017.